As the Canadian contingent of the group, I’ve been told my English skills are surprisingly good. As the resident translator, I’m here more for my disdain of poor grammar than any love for the group…

Once decided we would attempt the trails of the western Alps, there was just one problem: with which machine? It had to be old and have off-road pedigree. After a few evenings researching anything with knobby tires manufactured before myself, I was in love with the Yamaha DTMX. The effectiveness of its early monoshock rear is debatable, but with its high-mounted plastic fenders and long bench seat, the DTMX conjures images of the prototypical off-road machine. It certainly looked off-road-capable, and that’s the important part, right?

The holy grail was a DT400MX. But it became clear that everything on the market was either a basket case in beer crates, or in showroom condition – far too painful for the inevitable first crash of a rookie off-roader. The 250cc specimen rolled into view. One was found in the preferred colour scheme nearby. Though the price and condition seemed good, it quickly became a lesson in caveat emptor.

The bike had seen at least 9 previous owners and a move from somewhere counting in imperial units. The latest had planned to putter to his fishing pond, before realizing his knees were no longer built for kick-starting. The good: Despite 40 years of patina it was all-original, and had new tires, brakes, clutch and a relatively fresh MOT. And on a chilly November morning the engine sprang to life on just the second kick from cold! The bad: The DT had sat in a barn of unknown provenance for nearly 18 years. The ugly: the blinkers were hanging by threads and the seat was torn, though the friendly angler provided a new seat covering. After a quick test-drive, an acceptable price was haggled and the DT250MX loaded up.

Once home, the blinkers were replaced with modern flexible units, modified to accept 6v bulbs. The metal seat pan was found to be in critical condition, but was rescued through a combination of creative welding, riveting, and epoxy reinforcement. The seat covering was secured using seat spike strips.

The bike had already done 150+ problem-free kilometres, but all seals and cables were pre-emptively replaced, to avoid sitting victim to a 40-year-old consumable on the trailside. And here the fun began.

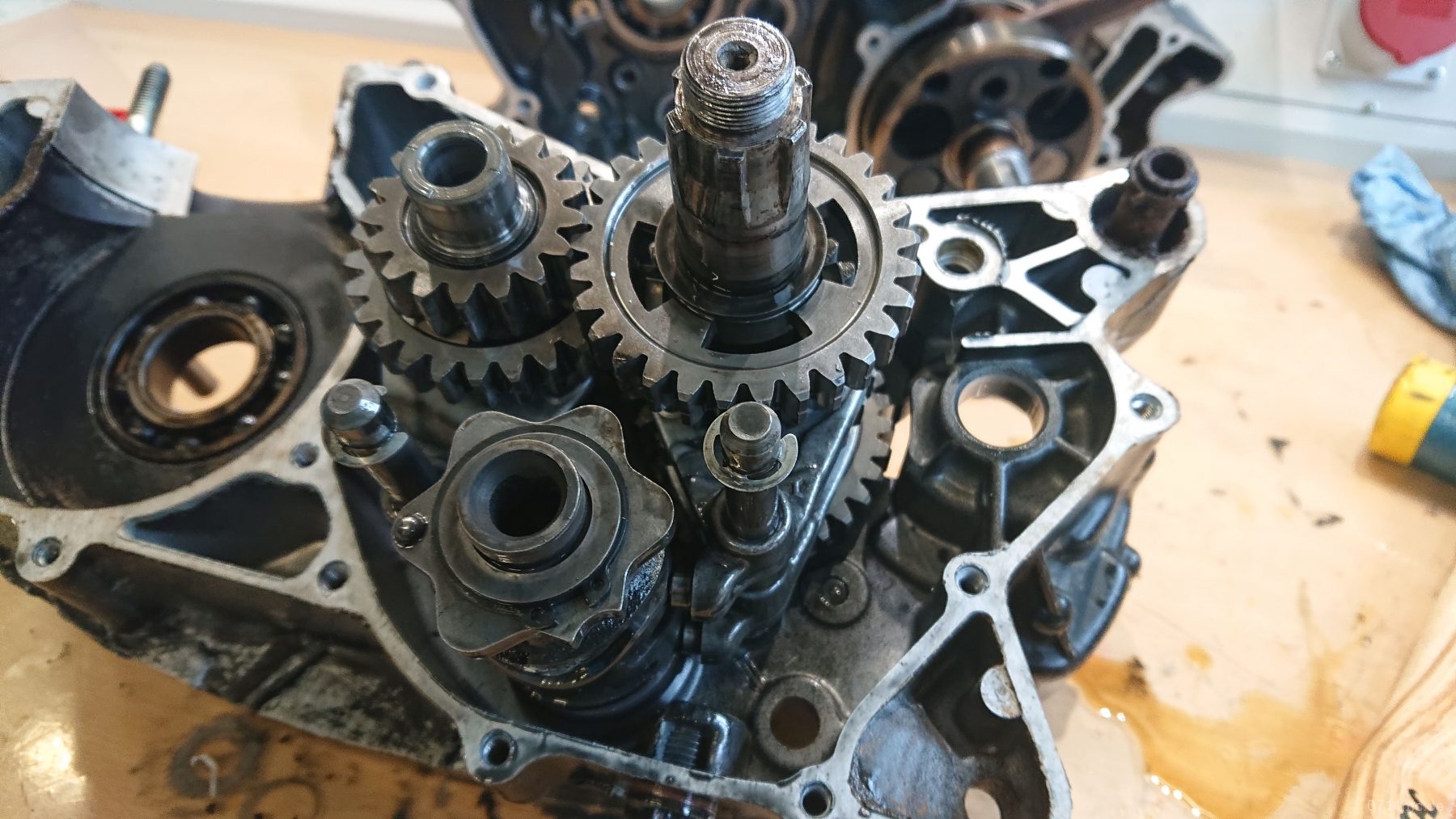

The air filter was found to be merely a sheer sock draped over the original cage and promptly replaced with a washable foam filter. A break in the transmission cover was found, likely caused by an overzealous Clarkson-type hammering on a stuck cover before checking that all bolts really were removed. The broken piece was welded in place and machined flat.

A curious glance into the exhaust port revealed an unholy sight: a deeply scratched and pitted piston skirt. The bike obviously still ran, but once seen, it could not be ignored if you want to cross Alpine passes without a constant niggling in the back of your mind. The top end came off and the cylinder was bored for the next piston size. And once there, who can resist pulling out the Dremel and optimizing those lumpy ports?…

Then it was off to Piedmont. A smoking headlight led to an impromptu deletion of the parking lamp. But more concerning was that a fork which had previously shown little indication of trouble under street use was now under significant loading, leaking oil like a BP drilling platform. There was much debate among colleagues whether the dark flecks on a boot were 10W or the traces of relieving oneself. Despite the issues, the DT was never left stranded. But it was clear – it required some much-earned TLC before the next adventure.

The forks were stripped down and sent for truing, then rebuilt and installed with an upgrade to tapered roller head bearings. Since then a few thousand kilometres have been travelled with no oil leakage. All rear suspension bearings were renewed and the lower shock axle replaced with a custom hard-chromed piece – the original had rusted after 40 years of neglect. Both shock axles were drilled to accept grease fittings, a maintenance-simplifying feature Yamaha should have implemented from the factory. The shock absorber was machined to accept dust seals from post ’79 models, as the pre ’79 seal design was discontinued. The chain tensioner, also overlooked by Yamaha engineers, was rebuilt with maintenance-free polymer bearings. Hidden bar ends machined from brass were shrink-fitted to the handlebars, serving the dual purpose of reducing vibration and adding a few centimetres of desired width.

An XL600R shift lever has been fitted, more conducive to modern motocross boots with a sprung end to avoid bending by stray stones. A 12v generator is being prepared after a number of moonless nights in Piedmont.

The experience with the DT250MX has been a learning relationship – particularly on what to inspect when purchasing the next bike. But there is a certain confidence going into an adventure one gains through having an intimate knowledge of every nut and bolt between your knees.

Workshop photos by https://shidhartha.de/

Seat spike strips: https://www.pandkclassicbikes.co.uk/

Air filter: https://unifilter.com/

Fork truing: https://www.roadrunner-bikeshop.de/

Tapered roller head bearings: https://www.allballsracing.com/

Maintenance-free bearings: https://www.igus.com/

12v generator: https://www.vape.eu/

Leave a Reply